Wi-Fi 6E Introduction

More than 20 years ago, when Wi-Fi was introduced, it opened up the first communication lanes in the 2.4 GHz band. We got around 80 MHz of unlicensed spectrum, which we can use for our wireless communication. Maybe a bit more, maybe a bit less, depending on the country you are in, and we do have to share it with other communication protocols. Bluetooth is probably the most known technology that also drives on this 2.4 GHz road. But it’s definitely not the only one, in microwaves, cordless phones or baby phones for example, we find other interferers in our channels. All of these together do make the road very congested and slow at times.

To avoid all these traffic jams, about five years later a new highway was opened in the 5 GHz band. This was a real game changer as we got around five times more lanes in this new band. Along the years, this was even expanded, and again the exact size depends on your country, but everywhere this was a huge increase in capacity. Just as in the 2.4 GHz band, Wi-Fi doesn’t get free rein here as well. Other technologies can equally make use of these channels, and some even have priority over Wi-Fi. On certain lanes, the rule is that if you detect radar traffic there, then you must move out of the way, and use another channel. That’s why a Wi-Fi access point must support DFS (dynamic frequency selection) if it wants to use these specific channels, to adhere to the rules of radar avoidance.

Of course as the years go by, we all keep on using more and more data, and eventually the 5 GHz band will no longer be enough as well. So the Wi-Fi world has lobbied for approval to build an extra highway, and as a result the regulators are opening up the 6 GHz band for unlicensed Wi-Fi usage. This is where we are building our newest, biggest, fastest highway, under the name of Wi-Fi 6E.

Wi-Fi 6E: the newest, biggest, fastest highway

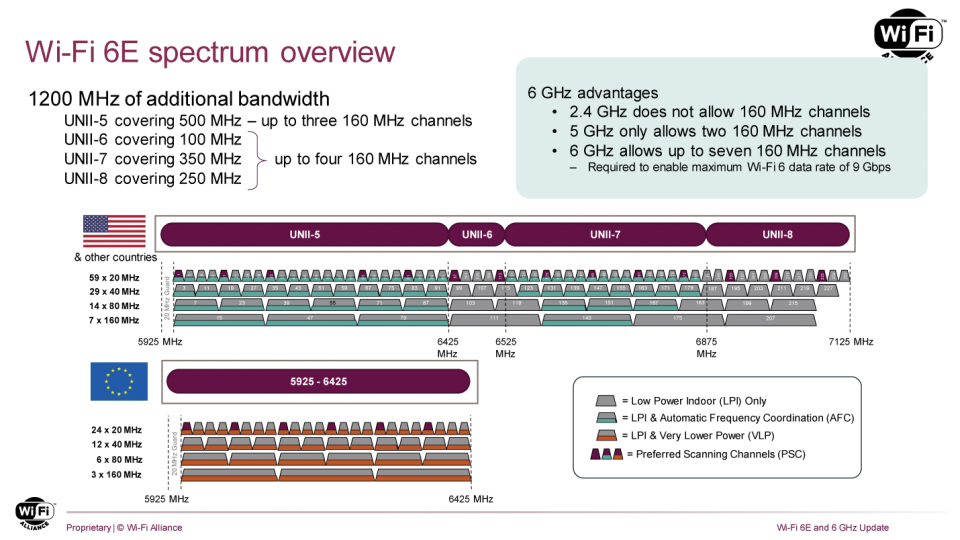

As for the other frequency bands, the spectrum allocation depends on the country you are in, and at the moment two approaches are taken. In the US for example the FCC allows the use of 1200 MHz between 5.925 GHz and 7.125 GHz, while in the EU only 480 MHz will be opened from 5.945 GHz up to 6.425 GHz. This corresponds with respectively seven and three 160 MHz wide Wi-Fi channels, roughly tripling or doubling the Wi-Fi capacity.

While this band consists only of non-DFS channels, meaning no radar avoidance as in the 5 GHz band is necessary, there are some incumbent services already using these frequencies. As for the radar communication in the 5 GHz band, these services must be protected as well, and three different approaches are proposed:

- With Very Low Power (VLP) the transmit power of the devices will be limited to very low values (14~17 dBm). As a consequence, the signals will have a small range, and hence also introduce minimal interference with the other services in this band.

- Low Power Indoor-only (LPI) devices will be allowed to transmit slightly higher (23~30 dBm), but still at power levels that can be considered low, and in this case only when they are located indoors. As the building surrounding the Wi-Fi devices, will dampen the signals going out, this will also result in very limited interference.

- A Standard Power device will be allowed to transmit at even higher levels (~36 dBm), but will have to make sure that there are no incumbent services nearby. For this to work, a centralized database with all the physical locations of existing 6 GHz communication links, needs to be available. An access point then has to validate first if in its region, the spectrum is free to use or not. The specifics of this are still under construction, but in the US such database is available, and by use of Automated Frequency Coordination (AFC) the access points will be able to do these location checks. In the EU, this is not as often available, and hence it is still unclear when or if these higher power values will be allowed.

By now it should be clear that this 6 GHz band is the newest, and definitely in the US also the biggest new highway, but it will also be the fastest, because only Wi-Fi 6 devices can use it. This means that no slower legacy devices can throttle our speed. We’ve got a new, big highway, ánd we only need to consider the newest, fastest Wi-Fi 6 devices on it.

In the US Wi-Fi 6E devices are already being certified, and hopefully later this year, we’ll see the same happening in the EU. All of this combined, makes this additional frequency band incredibly interesting and it is bound to set us up for the future. Especially with already the next Wi-Fi version in mind after 6, that will probably introduces even wider 320 MHz Wi-Fi channels.

To learn more about Wi-Fi, Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 6E, take a look at our Wi-Fi training offer!

Stay updated on the latest developments, subscribe to our newsletter.